Our Fascist Future

Fascism is once again rising around the world. The environment is ripe for strongmen and dictators to consolidate power over the masses. Yet, while many see what is unfolding and are aware of the dangers, as a society we are choosing fascism.

“If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.”

― George Orwell

Without steadfast nurturing, democracies die on the vine. If taken for granted, a bountiful society rapidly rots from the inside.

Elected into power, many fascist regimes grow organically from democracies. Fascists work the system to their advantage until they have the legal means to consolidate power. They may push the boundaries into extralegality, but without accountability the confines of legality loosen to the regime's advantage.

Today, as economic and environmental crises build, many countries around the world are unknowingly opening the door to fascism.

The 2020s could mark the end of democracy for many Western nations.

Why would voters and bureaucrats enable fascism?

First of all, nobody campaigns on a fascist platform. Voters must - but usually don't - listen the subtext of what politicians say. Also, (most) voters don't connect the outcome of an election to a violent regime. Or perhaps they see the possibility, but think they'll be unaffected.

Simply, voters choose the person who promises to make things better.

Usually, these voters are driven by fear. A profound national crisis, real or perceived, creates a sense of urgency and instability among the populace. This crisis can take various forms, such as economic depression, social upheaval, political deadlock, or perceived threats from external enemies or internal subversives.

In the face of such crises, fascist movements typically emerge by positioning themselves as the only force capable of restoring order and national greatness. They exploit these situations to create a narrative where traditional democratic institutions appear incapable of resolving the crisis, thereby justifying the need for more authoritarian, decisive leadership.

This pretext is often accompanied by the demonization of certain groups (like ethnic minorities, political opponents, or foreign nations), which are portrayed as responsible for the nation's woes. This scapegoating serves to unify the majority population against a common enemy and divert attention from more complex socio-economic issues.

Fascist regimes often capitalize on nationalistic sentiments, promising to revive a glorified historical past and restore the nation to its "rightful" place in the world.

The rise of Hitler in Germany post-World War I, Mussolini in Italy after economic and social turmoil, and Franco in Spain amidst a civil war are prime examples of how fascists have exploited national crises to dismantle democratic institutions and establish authoritarian regimes. In each case, the perceived failure of existing systems to deal with the crisis provided fertile ground for fascist ideologies to take root and flourish.

Fascism is once again on the rise

The world has problems. Some might call them profound.

- Massive wealth inequality.

- Unaffordable housing.

- High cost of living.

- Pandemic.

- Dramatic political polarization.

- Geopolitical chaos and rising threat of nuclear obliteration.

- Growing foreign military and economic competition.

- Biosphere destruction.

- Climate collapse.

Unfortunately, most of these problems will only worsen and people will increasingly feel the heat. Except for the 1%, everyone's standard of living will continue declining. So far it's been a slow burn, but we are approaching shocking events - widespread drought, multi-breadbasket failure - that will trigger widespread fear and panic.

The world is ready for fascism.

Fascism in 10 Easy Steps

The transition from a democracy to fascism can occur through a process where democratic structures and norms are gradually undermined and replaced by fascist ideologies and practices. This transformation is typically not abrupt. Instead, it generally takes 10 steps to transform a state from democracy to fascism:

1) Economic and Social Crisis: Fascism often gains traction during times of severe economic, social, or political crisis. Economic hardship, widespread unemployment, social unrest, or perceived threats to national security can create a fertile ground for fascist ideologies. These ideologies promise strong, decisive action to restore stability and national pride.

2) Exploitation of Fear: Fascist movements exploit existing fears, prejudices, and frustrations within a society. They often use propaganda to amplify these fears, blame societal problems on specific groups (like minorities or political opponents), and present themselves as the only solution to these problems.

3) Charismatic Leadership: Fascist regimes often emerge around a charismatic leader who claims to embody the will of the nation and promises to restore its greatness. This leader often uses populist tactics to appeal directly to the people, bypassing traditional political structures. The leader portrays themselves as a strong figure who can bring about national rejuvenation. This persona is built through public appearances, speeches, and a cult of personality.

4) Undermining Democratic Institutions: Democratic norms and institutions like a free press, an independent judiciary, and a functioning legislature are systematically weakened. Fascists discredit these institutions, reduce their powers and co-opt them to serve their agenda.

5) Cultivation of a Nationalist Identity: Fascism emphasizes extreme nationalism, often coupled with xenophobia, racism, or militarism. It promotes the idea of a homogenous national identity and suppresses diversity.

6) Suppression of Opposition: Gradually, opposition parties, labor unions, and other potential sources of dissent are marginalized, outlawed, or co-opted. Political rivals are often vilified, harassed, or even murdered.

7) Control of Media and Propaganda: Control over the media allows fascist movements to spread their ideology unopposed, glorify the leader, and manipulate public opinion.

8) Emergency Measures and Suspension of Rights: Emergency powers are used to deal with real or perceived crises, suspending civil liberties and democratic processes. Once suspended, these rights are often not restored.

9) Mobilization of Society: Fascist states often attempt to mobilize the entire society in support of their goals. This can involve mass rallies, educational programs, youth organizations, and intensive indoctrination.

10) Creation of a Police State: Fascists create a powerful and often brutal security apparatus - including secret police, surveillance systems, and laws that criminalize dissent - to enforce policies and suppress dissent.

Case study: Rise of the Nazi Party

The rise of the Nazi Party in Germany was a complex process, and it's debated how much the average German understood about the party's ultimate goal of establishing a fascist state. Initially, the Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, capitalized on the economic and political instability of the Weimar Republic, which was struggling with the aftermath of World War I and the Great Depression. The Nazis promised to restore Germany's economic prosperity and national pride, which resonated with many Germans who were disillusioned with the existing government.

The Nazi Party's ascent to power was gradual and involved both legal and extralegal means. In the 1930 national elections, the Nazis made significant electoral gains, becoming the second-largest party in the Reichstag, the German parliament. This success was partly due to their effective use of propaganda, which played on fears of communism and promoted nationalist sentiments. By 1932, the Nazis were the largest party in the Reichstag.

The turning point came in 1933 when Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg.

Adolf Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany was the result of a combination of political maneuvering and the unique circumstances of the Weimar Republic at the time. The Nazi Party, under Hitler's leadership, had become increasingly popular, capitalizing on public discontent by promising to restore order and national pride. Despite their popularity, the Nazis did not win an outright majority in the Reichstag elections, but they were the largest party. This electoral strength made them impossible to ignore in the formation of a government.

Conservative and nationalist politicians, including President Paul von Hindenburg and Franz von Papen, a former Chancellor, believed they could control Hitler and use his popularity to stabilize the government. They underestimated Hitler's political skill and ambition. On January 30, 1933, Hindenburg, under pressure from von Papen and other conservative elites, reluctantly appointed Hitler as Chancellor, hoping to form a right-wing coalition government.

This position allowed Hitler to consolidate power. He quickly took steps to dismantle the democratic structures of the Weimar Republic, starting with the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended civil liberties in response to a supposed communist threat.

This allowed the state to detain political opponents without trial, effectively suppressing Communist and other opposition. This decree was signed into law by President Hindenburg under the existing emergency provisions of the Weimar Constitution.

This was followed by the Enabling Act, passed in March 1933, which gave Hitler's government the power to enact laws without the consent of the Reichstag or President. The Act required a two-thirds majority to pass, which was achieved through a combination of Nazi seats, the support of other right-wing parties, and the suppression of communist and some socialist deputies (who were either arrested or intimidated). The Act effectively meant the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of Hitler's dictatorship, as it gave him the legal framework to rule by decree and dismantle the remaining democratic structures of Germany. The swift and strategic use of political power by Hitler and his allies, combined with the vulnerabilities of the Weimar Republic, facilitated Hitler's rise to dictatorial power.

Once in power, Hitler and the Nazi Party rapidly implemented policies aligning with fascist ideologies, including the suppression of opposition, control of the media, and the promotion of aggressive nationalism. The Nazis' aggressive foreign policy, aiming to expand German territory and undo the Treaty of Versailles, directly led to the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Hitler's invasion of Poland in September of that year, in defiance of international agreements, was the immediate trigger for the war.

How did Germans feel while their society slid into fascism?

Throughout this period, the extent to which the German populace understood the Nazi Party's full intentions is a subject of historical debate. Some Germans enthusiastically supported the Nazis, drawn by the promise of economic recovery and national rejuvenation. Others were apathetic, skeptical, or fearful but felt powerless to oppose the regime effectively.

Support for the Regime: A significant portion of the German population supported the Nazi regime, especially in the early years. This support was driven by various factors, including the successful propaganda campaign by the Nazis, the perception of economic improvement, the restoration of national pride, and the effective suppression of dissenting voices. The initial successes in foreign policy and the perceived restoration of Germany's status as a major power also bolstered support for Hitler.

Indifference or Passive Acceptance: Many Germans were either indifferent or passively accepted the Nazi regime. This group might not have actively supported the policies of the Nazis but did not oppose them either, often out of fear, apathy, or the belief that they could not change the situation. The effectiveness of Nazi propaganda and control over information also played a role in shaping public perception.

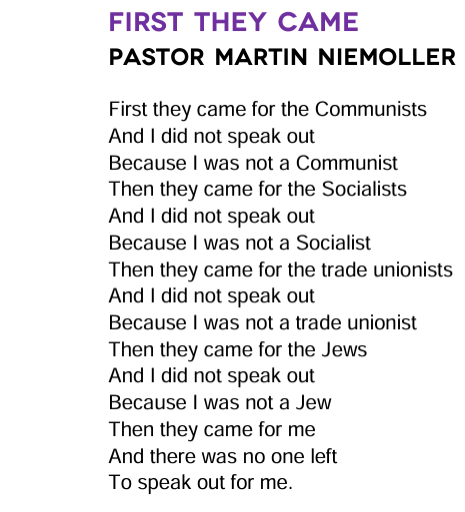

Opposition and Regret: There was also a segment of the population that opposed the regime, which included political opponents (like communists and social democrats), religious leaders, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens who disagreed with Nazi policies. However, expressing opposition was dangerous due to the repressive nature of the state, and many dissenters were arrested, sent to concentration camps, or forced to flee the country. Among those who initially supported the Nazis or were indifferent, some began to regret their support as the true nature of the regime became evident, especially as the war progressed and the atrocities committed by the regime became more apparent.

How common is fascism?

Throughout history power has repeatedly concentrated in the hands of the few. Monarchs, emperors and dictators are all cut from the same cloth.

Given the challenges of human existence, people often look to a greater power to solve their problems. Equity and progressive liberal values are the exception through history.

"Fascism is like a hydra - you can cut off its head in the Germany of the '30s and '40s, but it'll still turn up on your back doorstep in a slightly altered guise."

- Alan Moore

Below are just a few examples of fascist regimes in recent history:

- Italy under Benito Mussolini: In the post-World War I era, Italy was a parliamentary democracy. However, economic struggles, social unrest, and dissatisfaction with the results of the Treaty of Versailles created fertile ground for Mussolini's fascist ideology. In 1922, Mussolini was legally appointed Prime Minister by King Victor Emmanuel III. He gradually dismantled the democratic institutions, turning Italy into a fascist state by 1925.

- Spain under Francisco Franco: Spain's transition to a fascist state occurred after a bloody civil war (1936-1939). The Spanish Second Republic, established in 1931, was a democratic regime. However, deep political and social divisions led to the Spanish Civil War, with the Nationalists, led by General Francisco Franco, fighting against the Republican government. Franco's victory in 1939 led to the establishment of a fascist dictatorship, which lasted until his death in 1975.

- Japan in the early 20th century: While not a Western-style democracy, Japan in the early 20th century had elements of parliamentary governance alongside a strong imperial system. In the 1920s and 1930s, Japan saw a rise in militarism and ultranationalism, with military leaders and right-wing groups gradually undermining democratic institutions. By the 1930s, Japan had transformed into a militaristic state under Emperor Hirohito, with aggressive expansionist policies leading to its involvement in World War II.

- Portugal under António de Oliveira Salazar: Portugal became a dictatorship following a military coup in 1926, which dissolved the First Portuguese Republic. In 1932, António de Oliveira Salazar was appointed Prime Minister and established the Estado Novo ("New State"), a corporatist authoritarian regime. While not purely fascist, Salazar's regime shared many characteristics with fascist governments, including nationalism, anti-communism, and a strong police state.

Our fascist future

Over the past few decades, the Western middle class has slowly faded away. Measures of wealth disparity have worsened consistently, with the spoils of economic growth and asset price appreciation going to the 1%.

Some say this trend has persisted because of the liberalization of global labor markets and increased automation. Middle class jobs of decades past - e.g. manufacturing - have been outsourced to machines or inexpensive foreign labor. While the owners of capital benefited from a cheaper cost structure, many workers were left behind.

This alone has pushed ideologies of nationalism and popularism as people looked for someone to blame for their woes. Naturally, politicians - captured by corporate lobbying - never point to the true cause. Instead, they point to bogymen as the enemy. Immigrants, foreign countries, political parties, media are all now scapegoats for these economic woes.

As ecological collapse snowballs, this will only worsen. The destruction of the biosphere will have both physical repercussions and financial implications impacting the populace. Homes will be lost. Prices will rise. Food becomes more scarce and costly.

As we lose control and become poorer in physical and financial terms, the siren call of a savior will grow in appeal. A savior will say what we want to hear to get elected. And we will empower him with the undemocratic tools required to fulfill his promises.

But what will a fascist regime do when there's not enough food to go around?

With the consolidation of power comes the consolidation of wealth and resources. This small group in power will ensure what remains after crop yields plummet goes to feed them and their children. The masses will be left to starve or work as indentured servants in exchange for scraps. Most citizens will be viewed as "mouths to feed" in a time of scarcity. Liabilities, not assets.

By this time, the economy will probably be in shambles. Asset prices and economic activity decimated. This affects the wealthy as much as anyone else. However, in this fight for survival, physical wealth will supersede financial wealth. After all, money is simply the metaphorical representation of physical resources and labor.

So in place of financial wealth, those in power will stockpile physical assets and use the rest of society as indentured labor. Those who are not useful to either of those endeavors will be cast aside.

Coming to a democracy near you.